Henry and I extracted nearly 40 gallons of honey on Sunday. The early honey varietals that the bees produced are quite different from main season flows in many ways. First off, they taste different. As you can see in the photo above, early season honey contains a significant amount of pollen that we don’t filter out of the final product. The bees have been nectaring on species such as maple, chittum, native trailing blackberry, and poison-oak plus the hives that have been out on farms for pollination purposes serviced blueberries and raspberries. The flavors and colors of our five varietals from different seasonal apiaries vary quite a bit because of the nectar resources available in each of the locations, but they are all intense and distinct. As we were working away in the extraction room, the air became thick with an earthy, herbal smell that made me feel like I was getting some kind of health benefits just by huffing the aroma. If you’re looking for real, raw honey made from the nectar (and pollen) of Pacific Northwest native plants, this is the stuff you want.

Another way that this extraction is different than the ones we did last summer and the ones we will do later this summer is in the yield. When I pulled up my post on extraction from last summer to look at, Henry and I gasped at the top photo showing a beautiful, full frame of capped honey. The frames we were working with on Sunday were only ever partially full, and much of the honey was barely done curing and not yet capped. Many beekeepers don’t even bother extracting early honey because of the extra effort it takes to boost springtime honey production and the much lower yields per frame. With each frame being only 10% to maybe 80% full, each gallon of honey probably took twice as much handling and twice as much time invested as main-season honey.

One issue that can come up when extracting early honey, particularly uncapped honey, is too high of a moisture content. Honey must be cured to 18% (or less) water or else it can spoil over time. We tested out honey with a refractometer, and it came in at 16%, so we’re good.

Our beekeeper friend Ethan Bennett, owner of Honey Tree Apiaries, was generous enough to let us use his certified extraction facility again. We went through all the same steps as last year except we only scratched off the caps instead of using the flail uncapper.

In a trade like beekeeping, it’s hard to make it on your own as an owner/operator, so it really helps to have the support of fellow beekeepers. Henry and Ethan are able to share some resources and infrastructure, go in together on bulk orders, and help each other out in the field every once in a while. Ethan is also currently borrowing one of our flatbed trucks temporarily while he gets some work done on his.

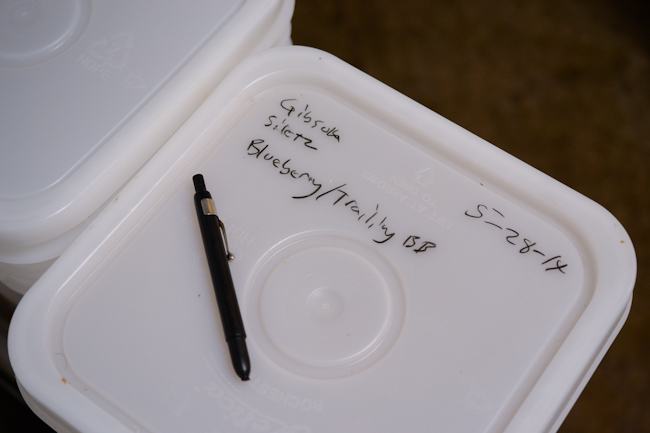

In the end, we will have just six to ten gallons of honey from each of Henry’s spring apiaries. While extracting, we did our best to keep the very small batches separate by draining the extractor between loads and being diligent about labeling the origins of frames and buckets of honey. We’ll begin bottling and selling the varietals hopefully within a month. This early honey will not be available in bulk quantities (though later honeys might be depending on our yield this year). I will be sure to make an announcement about when and where you can get your hands on this stuff. (Please be patient and refrain from emailing me with schemes about how I could sell you some early.)

Early Honey Extraction

Henry and I extracted nearly 40 gallons of honey on Sunday. The early honey varietals that the bees produced are quite different from main season flows in many ways. First off, they taste different. As you can see in the photo above, early season honey contains a significant amount of pollen that we don’t filter out of the final product. The bees have been nectaring on species such as maple, chittum, native trailing blackberry, and poison-oak plus the hives that have been out on farms for pollination purposes serviced blueberries and raspberries. The flavors and colors of our five varietals from different seasonal apiaries vary quite a bit because of the nectar resources available in each of the locations, but they are all intense and distinct. As we were working away in the extraction room, the air became thick with an earthy, herbal smell that made me feel like I was getting some kind of health benefits just by huffing the aroma. If you’re looking for real, raw honey made from the nectar (and pollen) of Pacific Northwest native plants, this is the stuff you want.

Another way that this extraction is different than the ones we did last summer and the ones we will do later this summer is in the yield. When I pulled up my post on extraction from last summer to look at, Henry and I gasped at the top photo showing a beautiful, full frame of capped honey. The frames we were working with on Sunday were only ever partially full, and much of the honey was barely done curing and not yet capped. Many beekeepers don’t even bother extracting early honey because of the extra effort it takes to boost springtime honey production and the much lower yields per frame. With each frame being only 10% to maybe 80% full, each gallon of honey probably took twice as much handling and twice as much time invested as main-season honey.

One issue that can come up when extracting early honey, particularly uncapped honey, is too high of a moisture content. Honey must be cured to 18% (or less) water or else it can spoil over time. We tested out honey with a refractometer, and it came in at 16%, so we’re good.

Our beekeeper friend Ethan Bennett, owner of Honey Tree Apiaries, was generous enough to let us use his certified extraction facility again. We went through all the same steps as last year except we only scratched off the caps instead of using the flail uncapper.

In a trade like beekeeping, it’s hard to make it on your own as an owner/operator, so it really helps to have the support of fellow beekeepers. Henry and Ethan are able to share some resources and infrastructure, go in together on bulk orders, and help each other out in the field every once in a while. Ethan is also currently borrowing one of our flatbed trucks temporarily while he gets some work done on his.

In the end, we will have just six to ten gallons of honey from each of Henry’s spring apiaries. While extracting, we did our best to keep the very small batches separate by draining the extractor between loads and being diligent about labeling the origins of frames and buckets of honey. We’ll begin bottling and selling the varietals hopefully within a month. This early honey will not be available in bulk quantities (though later honeys might be depending on our yield this year). I will be sure to make an announcement about when and where you can get your hands on this stuff. (Please be patient and refrain from emailing me with schemes about how I could sell you some early.)