It’s honey harvest time around these parts. In the Oregon Coast Range where Henry (doing business under the name Old Blue) has his remote apiaries, the nectar flow has pretty much dried up to a trickle even though there’s still plenty of pollen to be had. Henry is now working on preparing hives for the long winter by equalizing colonies, requeening if necessary, and beginning to feed syrup and pollen substitute. Most other commercial beekeepers are treating for mites right now, but Henry has chosen to manage his hives without standard miticide applications for the third season in a row. Without pesticides, there is more at stake, but Henry feels that natural mite loads put selection pressure on his colonies, and the resulting survivors express resistant traits reflected in the wild bee population.

This year, Henry worked hard to increase his number of hives by splitting stronger colonies, grafting queens, doing removals, and catching swarms, so honey production was not his primary focus. He also planned on leaving 60-70 pounds of honey in each full-size hive, more than the recommended 40-60 pounds, which should translate to a stronger colony buildup in the spring of 2014.

Because he can’t move colonies that are more than two boxes deep and because a strong colony doesn’t need more than two boxes of space to overwinter, he’s been splitting, equalizing, and consolidating hives and pulling excess honey from his largest 20 or so colonies that are each three to five boxes deep. Most of the hives that he planned on taking honey out of yielded 60-80 pounds each, but he also pulled a few frames of honey from hives that started the season as three-frame splits but increased better than he had expected.

We don’t yet have our own extraction equipment, but we were fortunate enough to have the privilege of using our friend Ethan of Honey Tree Apiaries state-licensed facility. Ethan is a great guy, and he sells his honey at the Corvallis Farmers’ Market every Saturday. You should go buy something from him if you get the chance. Ethan does not, however, rent out his place to anyone else for extraction. We just got in because Henry spent several very late nights helping him by hauling bees in and out of various pollinations and honey yards.

The night before we planned to extract, Henry brought the full boxes of honey down to Ethan’s place and moved them into the hot room adjacent to the extraction room to ensure that the honey would flow freely from the comb when spun in the extractor.

There are various ways to uncap comb and release honey from the wax-sealed cells. One of two methods we used was called “scratching”. We employed a special uncapping scratcher to rake over the comb, puncturing the cells.

Scratching is very controlled but somewhat slow and labor intensive. In the frames above, there was capped drone brood present in the middle of the honey-filled comb, and Henry was able to simply scratch around the brood so that it wouldn’t be extracted along with the honey.

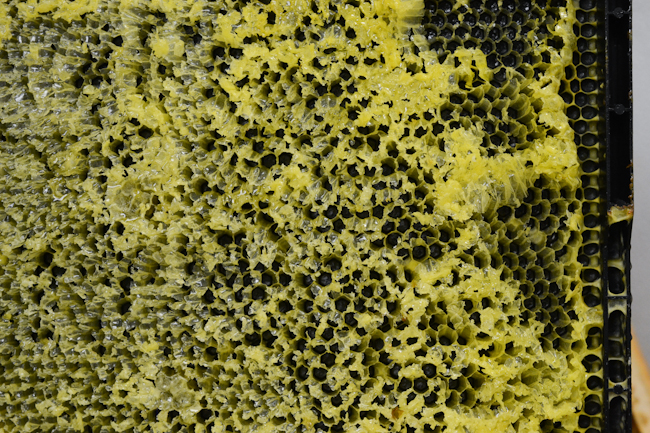

Ethan also has a flail uncapper that uncaps a whole frame in a matter of seconds. Ideally, an uncapper will simply remove or destroy the thin layer of wax on the outside of a frame, leaving the drawn comb intact to be used again after honey extraction. Flail uncappers work best on older, more durable comb, but as we discovered, they have a tendency to annihilate newer, still delicate comb.

After going through the flail uncapper, frames often had small patches of still-capped comb that needed hand scratching.

After uncapping, frames got loaded into a Dadant 20-frame radial extractor. With an extractor this large, it was important that the frames be inserted into the canister in a balanced order so that, like a washing machine, the centrifuge wouldn’t be thrown off balance while spinning.

Henry started the extractor out at a slow speed and ran it for five to ten minutes and then cranked it up to a higher speed for another five to ten minutes until there was very little honey being flung from the frames onto the sides of the canister.

While one batch was spinning, the next batch was being uncapped, so there wasn’t not a whole lot of down time in the process.

I took a little Instagram video of the whole process that you can see here (though it leaves something to be desired cinamatographily).

These slightly disheveled frames, empty of their honey, will be added back to hives soon. Bees will clean up and reuse these cells without expending a lot of energy and resources on creating wax for brand new foundation.

Honey extraction is a very messy, very sticky activity. Bits of wax fly everywhere, and the floor gets coated in a slippery film. Having a lot of stainless steel and concrete floors makes clean up a lot faster and easier.

A spout at the bottom of the extractor releases unfiltered raw honey as well as waxy bits into four-gallon food-grade buckets. In this extraction session, we got various shades of honey resulting from various different nectar sources.

Over time, the wax and other bee debris will float to the surface of the honey, and that top layer can be scooped out and melted down with the rest of the wax remnants.

Underneath the uncapper, there was a plastic tub with a screen filter on top that caught all the drippy uncappings with a considerable amount of honey mixed in.

Ethan has another nice centrifuge-type machine that can be loaded with the uncappings, and after spinning for 24 hours, it will separate out the honey from the wax. We just took our uncappings home in a bucket and will try to separate it by warming it up and letting the wax rise to the top in a big plug. We’ll keep that sub-par honey for our own home use.

There are screens and double doors on all the entrances to Ethan’s honey processing room. This time of year, hundreds of bees hover around the main door, actively trying to find a way into the facility to rob some sweet honey. One thing that really helps keep the bee mob out of the way is a fan in one of the screened windows. The fan blows honey scented air out on the back side of the building, drawing bees to that area and away from the front door. Try as they might, the bees can’t get in the window, and the room stays relatively bee-free.

After two extraction sessions, we now have about 100 gallons of honey that still needs additional filtering and bottling. A hundred gallons is a lot but not a LOT. Henry will give a significant portion of those stores away as “yard rent” (minimal compensation for a landowner’s permission to keep big batches of bees on his or her rural property), and we’ll gift some to friends and family. The rest we’ll sell. Henry’s going to have a box of pint jars full of honey in the back of his truck to sell to any interested horseshoeing clients, but we’re also working on developing other retail and wholesale opportunities. Eventually, we’d like to have an online shop, but we’re not quite there yet. In the meantime, my friend Halley is designing some nice labels for our jars (because we’re graphic-design-ily challenged), and we’ll be bottling honey soon.

Working at Honey Tree Apiaries is not a long-term solution for our honey extraction needs. Next year with more full-sized hives, Henry’s bees will hopefully produce a whole lot more honey, and we’ll need to get at least some of our own equipment and be more serious about sales. Henry’s been dreaming up plans for a mobile extraction facility housed in some kind of trailer with on-board water and a bicycle-powered extractor. (How groovy would that be?) I fantasize about something like the Provenance Farm mobile chicken butchering outfit only smaller. Whatever it ends up looking like, it will definitely be hoseable with plenty of stainless steel and not a lot of clutter. Ideally, we’d like to see a couple more extraction operations in action before investing in our own equipment.

I’ll be sure to let you know if/when Old Blue honey goes up for sale online. Until then, you should seek out a local honey producer in your area and get some of the sweet stuff for yourself.

Honey Extraction at Honey Tree Apiaries

It’s honey harvest time around these parts. In the Oregon Coast Range where Henry (doing business under the name Old Blue) has his remote apiaries, the nectar flow has pretty much dried up to a trickle even though there’s still plenty of pollen to be had. Henry is now working on preparing hives for the long winter by equalizing colonies, requeening if necessary, and beginning to feed syrup and pollen substitute. Most other commercial beekeepers are treating for mites right now, but Henry has chosen to manage his hives without standard miticide applications for the third season in a row. Without pesticides, there is more at stake, but Henry feels that natural mite loads put selection pressure on his colonies, and the resulting survivors express resistant traits reflected in the wild bee population.

This year, Henry worked hard to increase his number of hives by splitting stronger colonies, grafting queens, doing removals, and catching swarms, so honey production was not his primary focus. He also planned on leaving 60-70 pounds of honey in each full-size hive, more than the recommended 40-60 pounds, which should translate to a stronger colony buildup in the spring of 2014.

Because he can’t move colonies that are more than two boxes deep and because a strong colony doesn’t need more than two boxes of space to overwinter, he’s been splitting, equalizing, and consolidating hives and pulling excess honey from his largest 20 or so colonies that are each three to five boxes deep. Most of the hives that he planned on taking honey out of yielded 60-80 pounds each, but he also pulled a few frames of honey from hives that started the season as three-frame splits but increased better than he had expected.

We don’t yet have our own extraction equipment, but we were fortunate enough to have the privilege of using our friend Ethan of Honey Tree Apiaries state-licensed facility. Ethan is a great guy, and he sells his honey at the Corvallis Farmers’ Market every Saturday. You should go buy something from him if you get the chance. Ethan does not, however, rent out his place to anyone else for extraction. We just got in because Henry spent several very late nights helping him by hauling bees in and out of various pollinations and honey yards.

The night before we planned to extract, Henry brought the full boxes of honey down to Ethan’s place and moved them into the hot room adjacent to the extraction room to ensure that the honey would flow freely from the comb when spun in the extractor.

There are various ways to uncap comb and release honey from the wax-sealed cells. One of two methods we used was called “scratching”. We employed a special uncapping scratcher to rake over the comb, puncturing the cells.

Scratching is very controlled but somewhat slow and labor intensive. In the frames above, there was capped drone brood present in the middle of the honey-filled comb, and Henry was able to simply scratch around the brood so that it wouldn’t be extracted along with the honey.

Ethan also has a flail uncapper that uncaps a whole frame in a matter of seconds. Ideally, an uncapper will simply remove or destroy the thin layer of wax on the outside of a frame, leaving the drawn comb intact to be used again after honey extraction. Flail uncappers work best on older, more durable comb, but as we discovered, they have a tendency to annihilate newer, still delicate comb.

After going through the flail uncapper, frames often had small patches of still-capped comb that needed hand scratching.

After uncapping, frames got loaded into a Dadant 20-frame radial extractor. With an extractor this large, it was important that the frames be inserted into the canister in a balanced order so that, like a washing machine, the centrifuge wouldn’t be thrown off balance while spinning.

Henry started the extractor out at a slow speed and ran it for five to ten minutes and then cranked it up to a higher speed for another five to ten minutes until there was very little honey being flung from the frames onto the sides of the canister.

While one batch was spinning, the next batch was being uncapped, so there wasn’t not a whole lot of down time in the process.

I took a little Instagram video of the whole process that you can see here (though it leaves something to be desired cinamatographily).

These slightly disheveled frames, empty of their honey, will be added back to hives soon. Bees will clean up and reuse these cells without expending a lot of energy and resources on creating wax for brand new foundation.

Honey extraction is a very messy, very sticky activity. Bits of wax fly everywhere, and the floor gets coated in a slippery film. Having a lot of stainless steel and concrete floors makes clean up a lot faster and easier.

A spout at the bottom of the extractor releases unfiltered raw honey as well as waxy bits into four-gallon food-grade buckets. In this extraction session, we got various shades of honey resulting from various different nectar sources.

Over time, the wax and other bee debris will float to the surface of the honey, and that top layer can be scooped out and melted down with the rest of the wax remnants.

Underneath the uncapper, there was a plastic tub with a screen filter on top that caught all the drippy uncappings with a considerable amount of honey mixed in.

Ethan has another nice centrifuge-type machine that can be loaded with the uncappings, and after spinning for 24 hours, it will separate out the honey from the wax. We just took our uncappings home in a bucket and will try to separate it by warming it up and letting the wax rise to the top in a big plug. We’ll keep that sub-par honey for our own home use.

There are screens and double doors on all the entrances to Ethan’s honey processing room. This time of year, hundreds of bees hover around the main door, actively trying to find a way into the facility to rob some sweet honey. One thing that really helps keep the bee mob out of the way is a fan in one of the screened windows. The fan blows honey scented air out on the back side of the building, drawing bees to that area and away from the front door. Try as they might, the bees can’t get in the window, and the room stays relatively bee-free.

After two extraction sessions, we now have about 100 gallons of honey that still needs additional filtering and bottling. A hundred gallons is a lot but not a LOT. Henry will give a significant portion of those stores away as “yard rent” (minimal compensation for a landowner’s permission to keep big batches of bees on his or her rural property), and we’ll gift some to friends and family. The rest we’ll sell. Henry’s going to have a box of pint jars full of honey in the back of his truck to sell to any interested horseshoeing clients, but we’re also working on developing other retail and wholesale opportunities. Eventually, we’d like to have an online shop, but we’re not quite there yet. In the meantime, my friend Halley is designing some nice labels for our jars (because we’re graphic-design-ily challenged), and we’ll be bottling honey soon.

Working at Honey Tree Apiaries is not a long-term solution for our honey extraction needs. Next year with more full-sized hives, Henry’s bees will hopefully produce a whole lot more honey, and we’ll need to get at least some of our own equipment and be more serious about sales. Henry’s been dreaming up plans for a mobile extraction facility housed in some kind of trailer with on-board water and a bicycle-powered extractor. (How groovy would that be?) I fantasize about something like the Provenance Farm mobile chicken butchering outfit only smaller. Whatever it ends up looking like, it will definitely be hoseable with plenty of stainless steel and not a lot of clutter. Ideally, we’d like to see a couple more extraction operations in action before investing in our own equipment.

I’ll be sure to let you know if/when Old Blue honey goes up for sale online. Until then, you should seek out a local honey producer in your area and get some of the sweet stuff for yourself.